For many Lawrence folks, especially those that frequent Saturday farmers market, the Pollinators mural and its untimely demise are still fresh in their memories. News that the mural would have a second life was celebrated but also prompted many questions. Where would the new mural be located? Would it be the same size? Who would design and paint it? And most crucially, would the design be the same, including the seven African-American artists and the Gwendolyn Brooks quote, “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond”?

Answering the first three questions was easy. The new mural would be at the same relative location (the north facing wall adjacent to farmers market), although only about half as large. The muralists, as I mentioned in our previous blog post, would be comprised of both new and old design team members plus a new assistant and two new apprentices. Much more difficult to answer is the last question - how would the design be different from the original, what would remain, what would be changed, and what would be added?

Since early February, our design team has been grappling with these questions. Early on we chose to not merely reproduce the original Pollinators, but to re-imagine it. We committed to honoring the original while adding elements that speak to a new time and new circumstances.

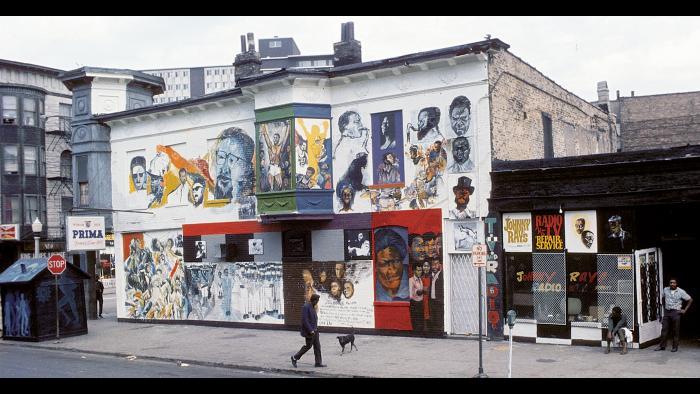

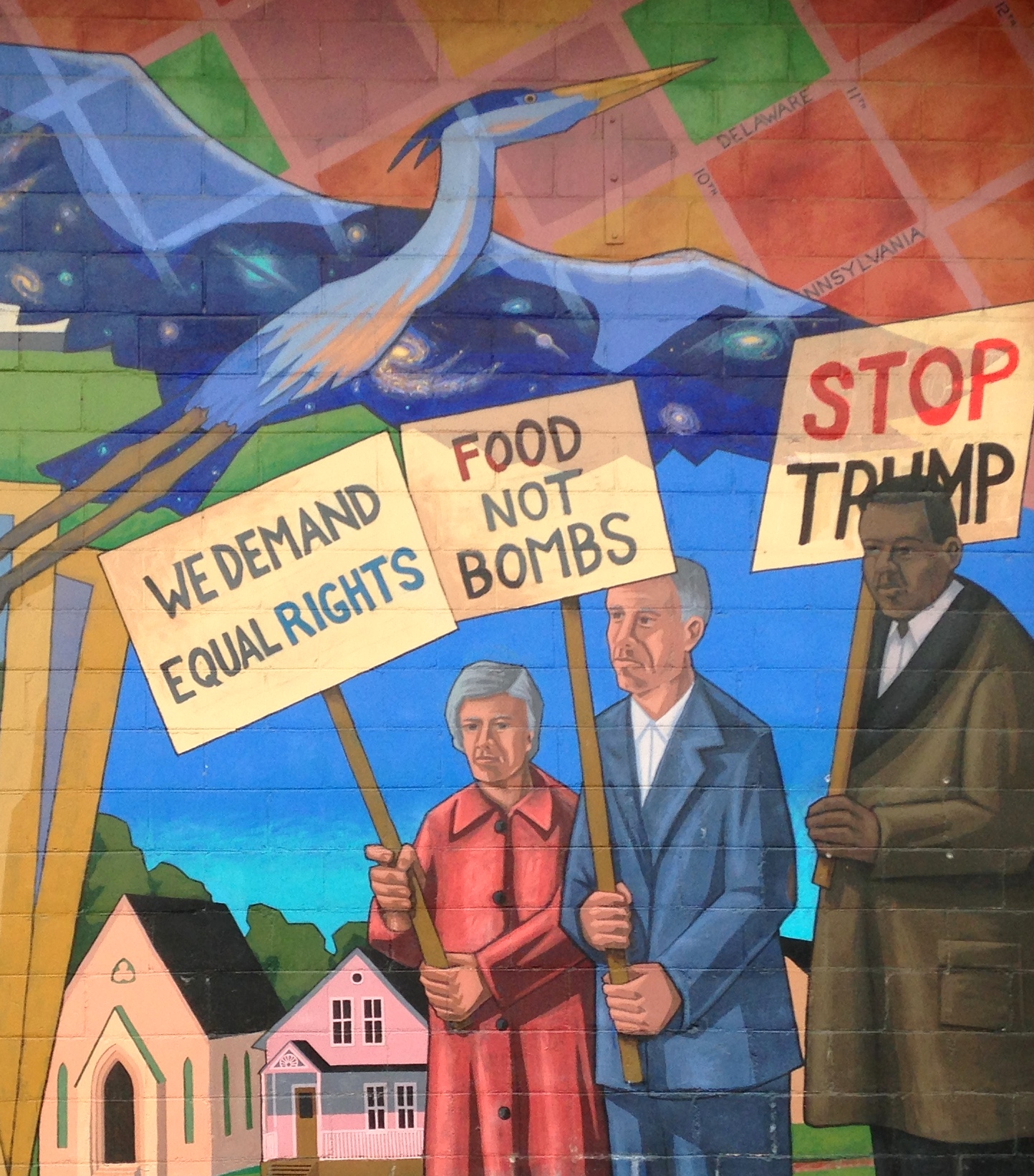

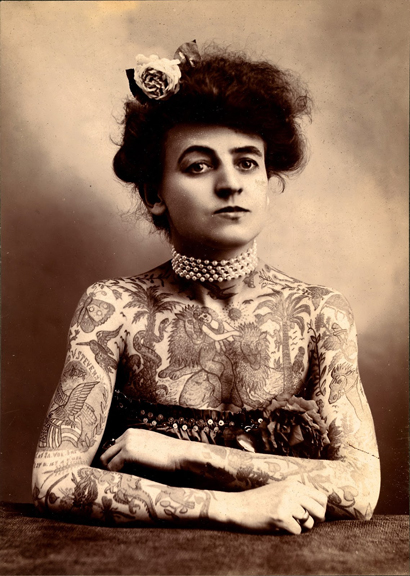

There are a few precedents for re-imagining a mural. The iconic “Wall of Respect” in Chicago, which evolved over the years with some images being replaced with others as needed, is probably the best known.

The "Wall of Respect" in Chicago, Illinois.

The idea that a mural does not necessarily have to be static or ever really finished, that it can be a living expression that grows and changes with the times has been a compelling notion for our design team. Because visual art is bought and sold as a commodity, there is less opportunity to change something after it's left the studio, while re-imagining artworks in other media like dance and theater is much more familiar. It’s not uncommon to see reinterpretations or updated versions of well-known stories from the likes of Shakespeare or August Wilson set in new contexts with casts that reflect different points of view. We have that opportunity because the Pollinators is being recreated and we can make changes if we wish. It would be a much different story for folks at the Spencer Museum and City, I imagine, if the original mural was still there and we proposed to change and adapt it.

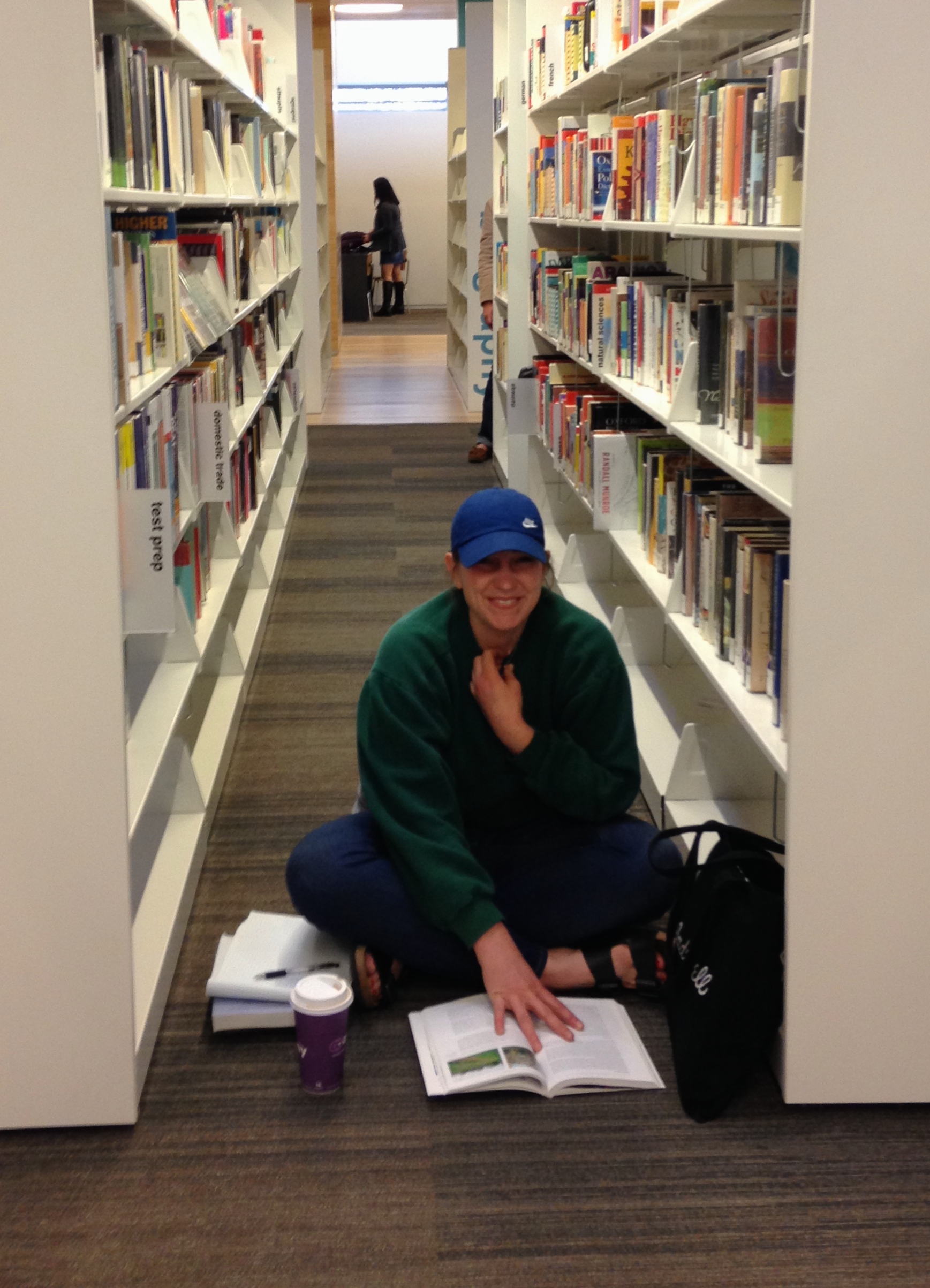

To ground our re-imagining, we began at the Lawrence Public Library with research about the original Pollinators, it’s subject matter and design, and how the community came together to ensure it would rise again.

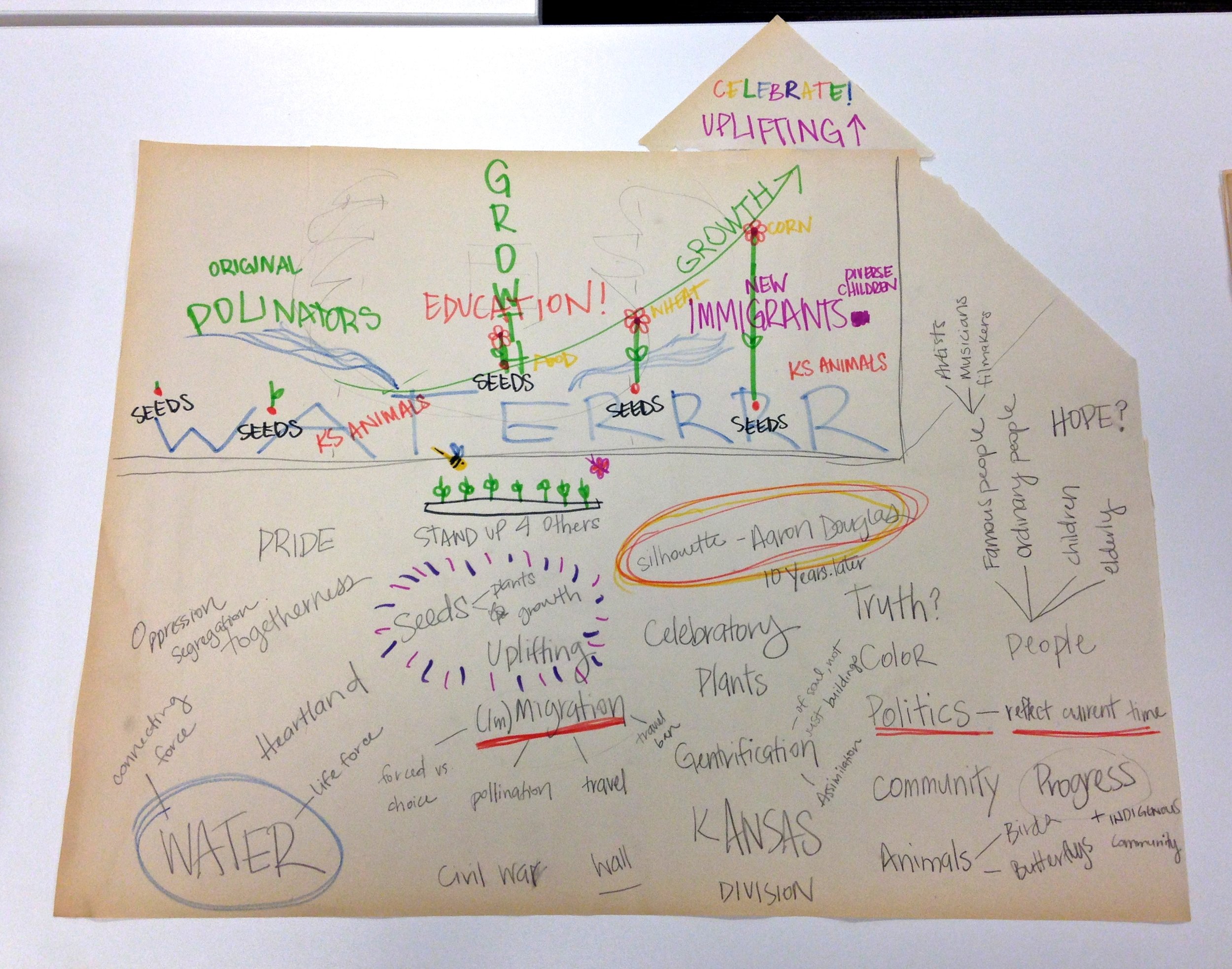

The team felt strongly that this story of why the mural was destroyed and the community effort to restore it needed to be depicted in some form. The fate of the Pollinators is connected to the larger story about how downtown Lawrence is changing and who will benefit from those changes. Re-examining the central metaphor from the original mural, we began thinking about the factors, agents, etc. that inhibit or block pollination in nature. This led us to question what factors might inhibit the ability of the artists depicted (and their descendants) to ‘pollinate’, and how analogous forces could prevent cultural cross-pollination in the larger community. Big questions.

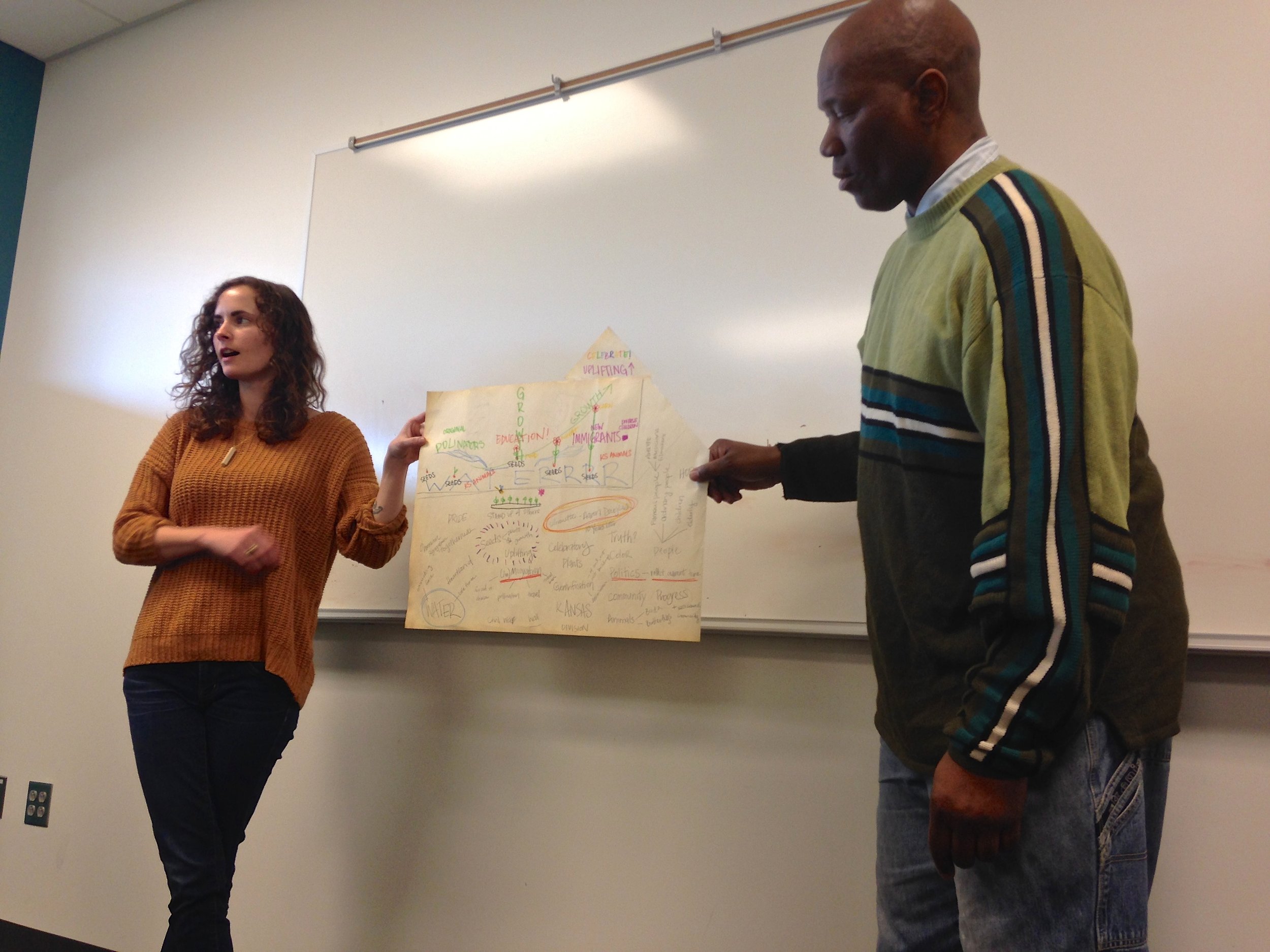

So, instead of separating our discussion about the biology of pollination from the African-American artist pollinators in the mural and the cultural impact of new development, we let these ideas overlap, complicate and influence each other. We talked about monoculture in agriculture and how to spot signs of monoculture within the cultural community of Lawrence. We talked about the shape and structure of pollen grains, the persistence, beauty and utility of 'weeds', contemporary African-American artists with roots in Kansas, and we talked about how upscale development is encroaching on the East side with uncertain consequences. Our research and conversations produced a wealth of ideas.

In this way, the re-imagined Pollinators project has become a forum for creatively addressing important issues including affordable housing, food justice, and people’s history. This is intentional. Inspired by the examples of artists Liz Lerman, Augusto Boal and Judy Baca, our approach is founded on the idea that a collaborative creative process can illuminate and articulate community conflicts and aspirations in ways that can lead to equitable and just solutions.

Next, we begin to visualize the mural design…