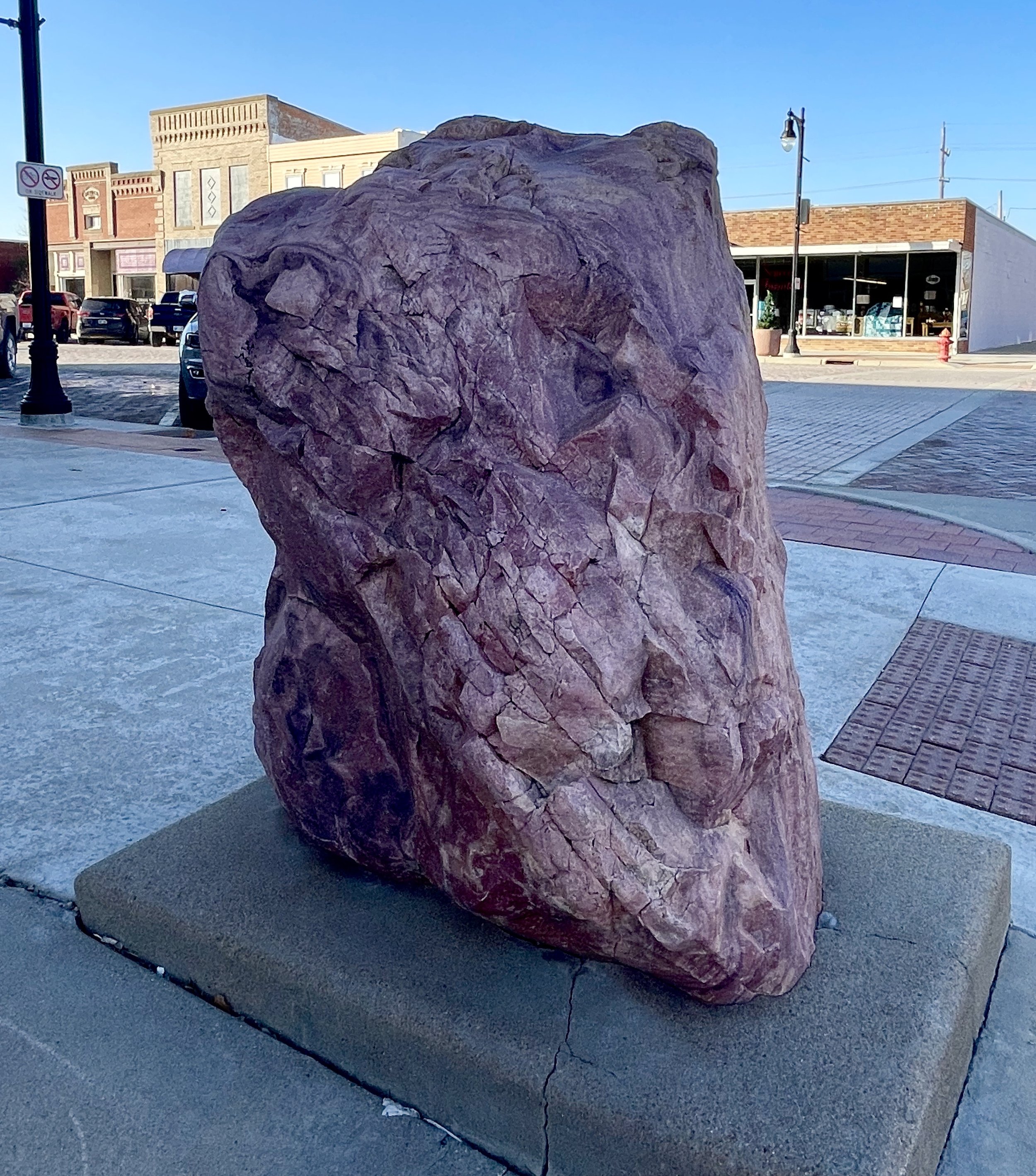

This series of prints began with a small mystery. I wondered how the large pink stone (over three-hundred pounds) that sat between the alley and garage door of my studio got to where it was. It didn’t appear to serve a function in relation to the building or have a decorative purpose, but it was too big to not have been placed there intentionally, I thought. For more than twenty years I’d speculated, usually when I had to get around it to take out the garbage or when rain turned its surface into a deep maroon flecked with a constellation of white crystals like a giant gumdrop, who would have put it there.

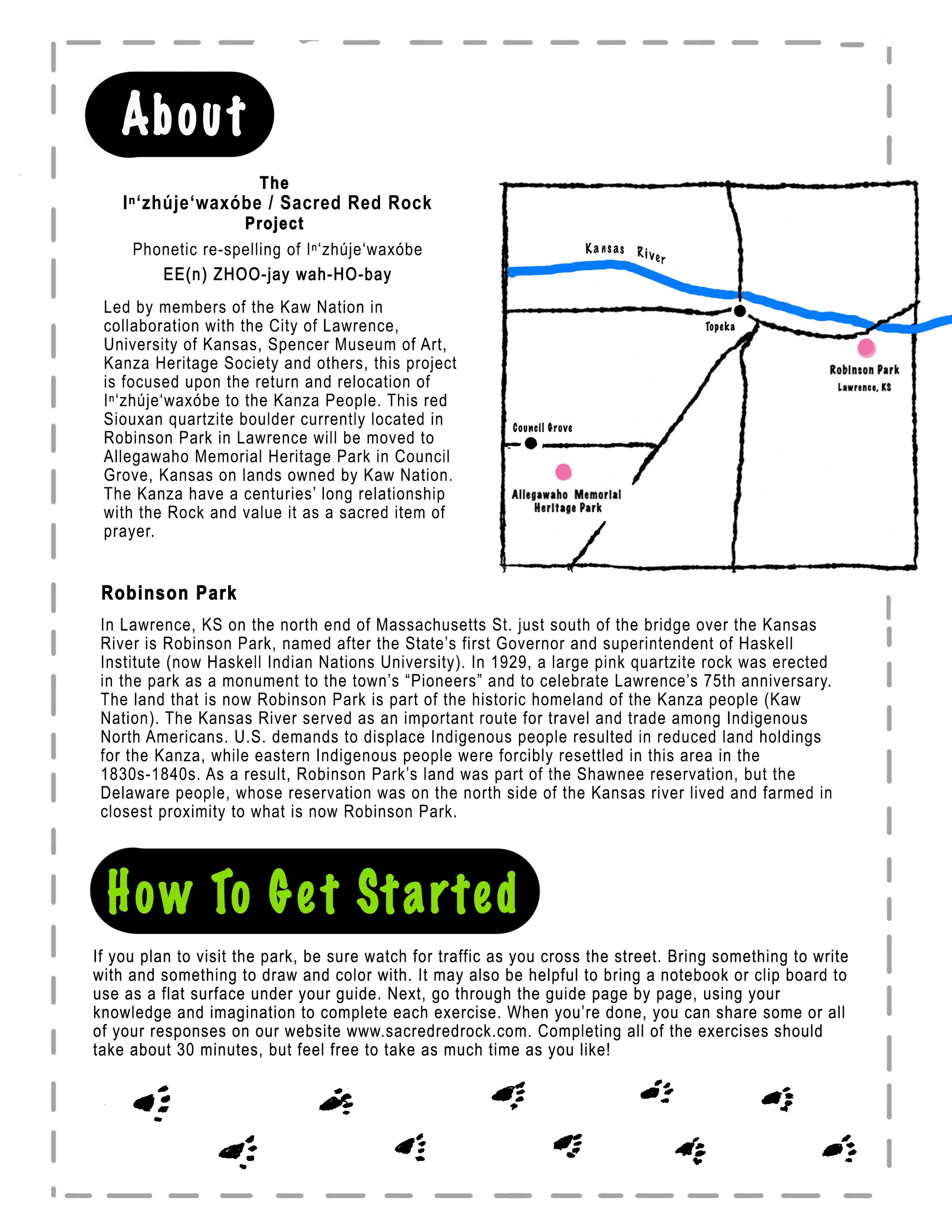

The answer didn’t occur to me until I began working with Pauline Sharp on what we called, at the time, the “Between the Rock and Hard Place” project, and that was that the stone had not been placed there by people but by nature. The Sacred Red Rock ( Iⁿ‘zhúje‘waxóbe ) that we were working to bring attention to and the boulder in front of my studio were both red quartzite glacial erratics, survivors of earth’s early years that had hitched a ride on a glacier during the last ice age from what we now call South Dakota and ended up in Kansas.

What for me had been a simple rock and sometimes nuisance became a direct connection to primordial forces, embodied with characteristics of strength, beauty and perseverance. Learning this expanded the story I had about the place where I lived, in the same way that learning the location of the North Star in the night sky had changed the way I thought about outer space when I was a kid. After solving the mystery, I began to see these stones in places I hadn’t before, as if they’d been hidden or camouflaged by my simple lack of regard.

More conspicuous than concealed, I’d find them serving as bases for monuments in town squares and city parks. There were monuments to The Settlers, the Pony Express, the Oregon Trail, to the military, to philanthropists and even a monument to the glacier itself in Blue Rapids. But the one that inspired this series had an added feature that showed how people-built landscapes can create unintended juxtapositions that reveal truths otherwise obscured by the language of committee approved bronze plaques.

It was a dome shaped glacial erratic in Kansas City’s Penn Valley Park, embedded in the ground and rising up about four feet with a small bronze plaque on its face honoring the writer of the book, “The Annals of the City of Kansas and the Great Western Plains,” published in 1856. It’s an unremarkable monument, out of place and without context in the way many attempts at memorialization can gradually lose their relevance as time passes. But then I noticed, as I kneeled down to take a photo, that if you look at this stone from a certain angle, the iconic Kansas City statue known as “The Scout” appears to standing in miniature right on top of it.

“The Scout” like the glacial erratic stone it appeared to be standing on were both originally from somewhere else – the stone from up north, and the subject of the statue, a Sioux scout, from their Tribe and Land. Seeing them together as unintended immigrants, removed from their homes by nature on one hand and by human interference on the other, inspired the first print in this series. The others, which all depict actual stones in northeast Kansas, were similarly influenced by the admiration (sometimes misplaced) that humans seem to have for these ancients and how we have tried to weave their majesty into our own stories.