It’s getting lighter. Daylight savings time is back. Mural season. Flowers awaiting pollination are beginning to bloom, daffodils and dandelions first. Bees are appearing and monarchs have begun their migration north from Mexico. There’s front-page news in the Journal-World that a fraternity of eighty-seven guys has moved into the 888 New Hampshire building (where our mural will be), while their palatial estate was being renovated. Closing in on the north side of the farmers market parking lot, construction continues on a yet another upscale apartment building shrinking evermore the neighborhood’s habitat for affordable housing.

In the studio a couple blocks away, we began imagining how the Pollinator artists would have responded to the destruction of the original mural, and how they would feel about changes to the neighborhood. Would they act to protect and defend natures’ pollinators against threats to their habitat? How would they respond to the new building on which they would be painted and what it signaled for the East side of Lawrence? Would other artists be compelled to join them in their struggle?

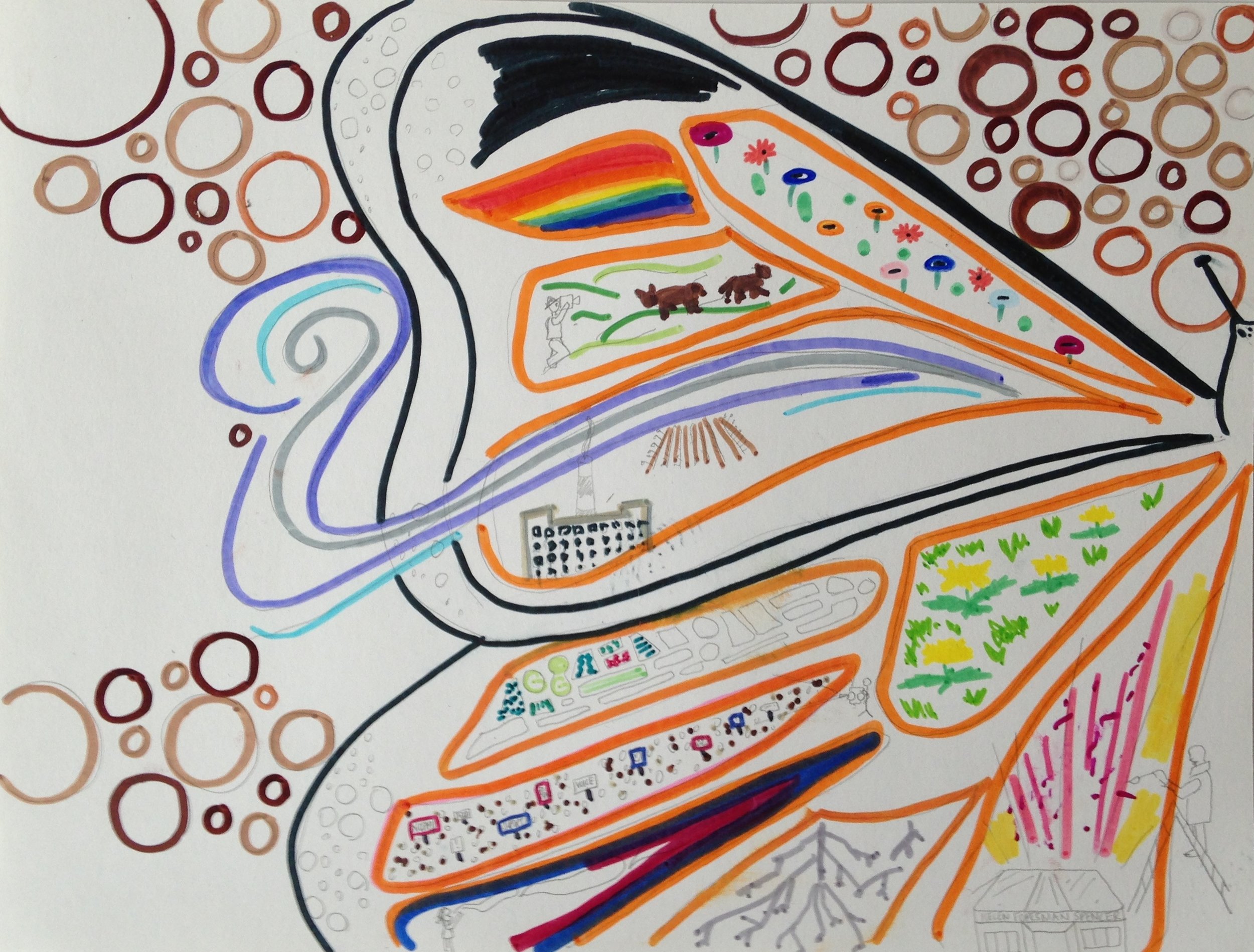

Our initial drawings illustrate a tension between competing ideas about how neighborhoods develop and change, and who or what affects that change. As we worked, we talked about the tools and strategies artists posses to address these issues - how music, poetry, film and painting can shift perceptions and inspire action.

As space for affordable housing shrinks near downtown, so does the habitat for nature's pollinators. Market driven monoculture has replaced many wild and organic backyards and greenspaces in Lawrence with chemically enhanced weed-free sod. Dandelions are the enemy, technology the solution as with these newly developed 'drone pollinators.'

This kind of erasure isn't new. Mural Assistant Nedra Bonds has seen it before. In the 1980's, the historic site of Quindaro, near Nedra's home in Kansas City, Kansas, was nearly turned into a trash dump. No one in power seemed to care that Quindaro had been established by Wyandots and Abolitionists to fight pro-slavery forces until Bonds and others started to make a fuss and tell the story through quilts. It is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Nedra sharing her Quindaro quilt at our Design Team workshop

So what's the antidote to market driven monoculture? Wes Jackson at the Land Institute calls it perennial-polyculture, a practice of mimicking the prairies of central Kansas to produce crops that don't require the soil numbing toxins used in industrialized agriculture. We asked ourselves what a perrenial-polyculture of built structures and human community would look like in Lawrence. Our answer meant aligning the mural design with wind-blown seeds, weeds and migrating pollinators both human and winged who eschew monotone and monochrome for a full spectrum of experience.